When Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neil coined the term “BRIC” in 2001, it was to highlight the bright future among the largest Emerging Market (EM) Economies. Indeed, the MSCI EM has grown more than 400% since 2001, in line with the S&P 500’s growth of 420%. But since the BRICS officially started meeting in 2006, divergent economic trajectories have transformed the bloc from one of economic cohesion to a one where each member uses the platform to advance their own agenda. The last three years have been especially difficult for the BRICS, with market downturns in China, Russia, and South Africa weighing on the group’s performance. Since 2020, markets have fallen on average 8% against the S&P 500’s 10.5% gain.

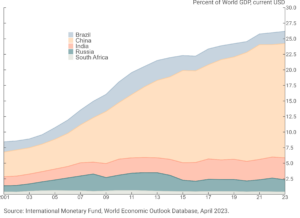

BRICS Performance has largely been driven by China’s economic boom

This year’s meeting could not have come at a worse time, particularly for China. Despite lowering interest rates and some stimulus measures, China’s economy and local consumption are not having the expected bounce. The property market remains weak and youth unemployment – which the government has since stopped reporting – reached a record high of 21.3% in July. Waning investor optimism has pushed markets down 52% from 2021 highs and caused foreign investors to flee – Chinese funds have seen more than $11 billion in outflows this month alone. Though current longer-term growth expectations still hover around 4%, it would be unsurprising if this comes closer to 3% given the recent trends.

On the other hand, timing might have been just right for India, where stellar growth this year has attracted attention and significant capital inflows. Markets have gained 6.1% year-to-date while Q1 GDP surged to 6.1% on a YoY basis. Policy changes, ongoing infrastructure development, and a promising demographic dividend have been instrumental in India’s emergence. While they may not be able to achieve the same growth China had over the past five decades, India’s recent rise may have the country feeling more comfortable about its position within the bloc.

China’s growth unmatched by the other BRICS countries

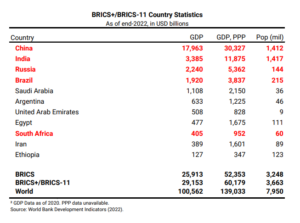

The addition of six new members was much more about consolidating political interests than growing an economic bloc. This is clear in the countries invited to join. They have little in common with each other except in having some grievance against the West. For President Xi Jinping, the driving force behind the decision, this was an important win for growing China’s sphere of influence and challenge the existing global order. It also opens the door to other countries that would help China’s geopolitical aspiration to move away from Western dominance.

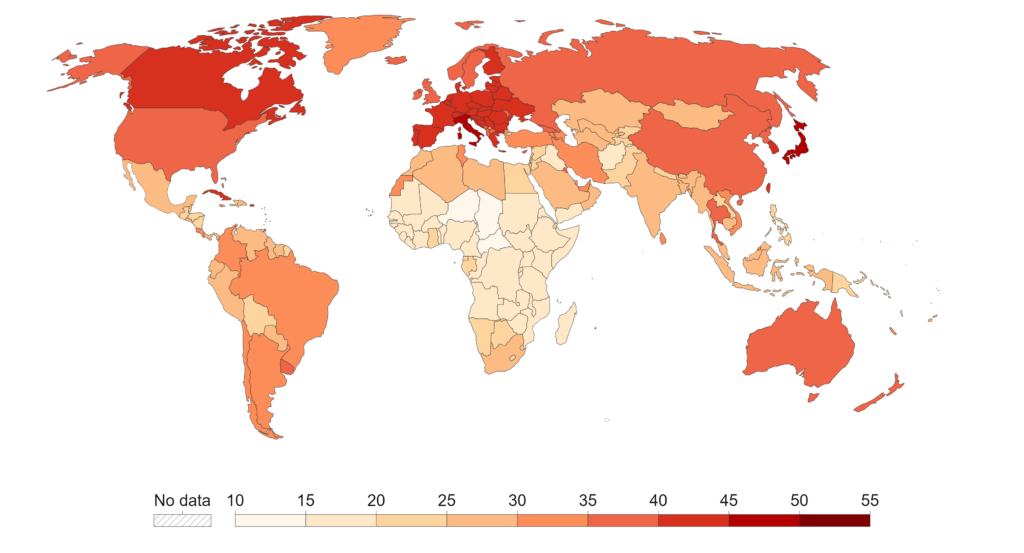

The bloc faces an uphill battle if it wants to become a formidable counterweight to the West and champion of the Global South. Despite accounting for one-third of global economic activity (as measured by purchasing power parity), the BRICS’ recent economic woes do not bode well. With or without the expansion of the BRICS, China’s role in global trade will likely be diminished in the future. South Africa is struggling with rolling energy blackouts and high youth unemployment, while Brazil’s economy has slowed markedly since the days of the commodities boom. Meanwhile, Russia is all but shunned in international markets (President Putin was unable to join this year’s summit due to an outstanding warrant arrest). The BRICS Bank’s anemic lending and inability to help Russia in its time of need reveals how ineffective the countries are as an economic bloc.

The BRICS may grow as a symbolic presence, but the new members add very little in terms of economic power. They open up some consumer markets, but they generally are small in population size. Mostly, expanding the group will also introduce more internal conflict. Argentina and Egypt are large IMF borrowers, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE are traditional military allies of the West. Iran has its own sanctions to navigate. It is unlikely that the BRICS – or whatever name they use as a replacement – will transform into an effective and coherent group any time soon.

Emerging markets still represent interesting investment opportunities – just not as a BRICs entity. Moderating inflation, monetary easing steady currencies, and a growing consumer base lend to their attractiveness. Africa’s population, like India, is also young, full of untapped potential, and expanding rapidly. With the right investment and reforms, Africa’s youth can drive sustainable development and power the global economy. Opportunities in the digital transformation space, such as Fintech and AI, continue to grow and present exciting opportunities not just for Africa’s growth but also for other EMs in Latin America, ASEAN, and Eastern Europe. These markets may be subject to the whims of global macro conditions that make investing in EM a moving target, but the longer-term outlook remains promising.